I was involved in a conversation last night on the Book Creator Ambassador community site about ethics and edtech. I promised I’d write about my views and so here is the post…

Back in 2017, the New York Times ran an article highlighting the potential ethical issues around brand ambassadorships. In the article ‘Silicon Valley Courts Brand-Name Teachers, Raising Ethics Issues‘, author Natasha Singer comments:

“The benefits to companies are substantial. Many start-ups enlist their ambassadors as product testers and de facto customer service representatives who can field other teachers’ queries.”

This though brings up the issue of ethics. As Singer highlights:

“Public-school teachers who accept perks, meals or anything of value in exchange for using a company’s products in their classrooms could also run afoul of school district ethics policies or state laws regulating government employees.”

The same is true here in the UK.

Singer’s article is excellent, well-researched and uses existing brand ambassadors and influencers in her article to discuss the issues surrounding all of it. I wrote about it at the time in this post: ‘Ambassador You’re Really Spoiling Us!‘

It’s not the first time the issue of ethics has been discussed either. As noted back in 2016 by David Didau in a series of posts, he shares the following about vested interests and edtech ambassadors:

“When somebody criticises something in which you have a vested interested it’s very hard to remain dispassionate.”

I am someone who is an ADE (Apple Distinguished Educator), GCI (Google Certified Innovator) and hold other ambassador roles with other edtech solutions such as Book Creator, Nearpod, Showbie and even more than that. Given this and my current job working for myself, I understand more than most the many the issues for conflict that can arise. As Didau recognises about applying for ADE:

“…let’s imagine I’d been able to apply and got accepted. What then? How, if I’m going around advocating “the use of Apple products that help engage students in new ways” am I going to remain non partisan? What if, for instance, I thought the new kit from Samsung or Microsoft was better than the Apple products I was advocating? Would I feel able to say so? How would Apple react if I advocated someone else’s products?”

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) officially issued guidance that any ambassador or influencer must disclose their relationship with a company when making any social media posts that promote a product or service. They offer some great advice here, and they have also created a really useful infographic to help make the guidelines clear too:

The detail and length of this infographic clearly demonstrates what a minefield this can be for teachers.

Interestingly, the FTC’s guidelines are very much in line with guidance from the UK’s ASA (Advertising Standards Authority) who have as their strapline “Legal, decent, honest and truthful” which states:

“Obviously, if you’re paid a specified amount of money to create and/or post a particular piece of content, this counts as ‘payment’. But this isn’t the only type of arrangement that counts. If you have any sort of commercial relationship with the brand, such as being paid to be an ambassador, or you’re given products, gifts, services, trips, hotel stays etc. for free, this is all likely to qualify as ‘a payment [or other reciprocal arrangement]’. There’s nothing wrong with getting paid to create content and this alone doesn’t make it an ad for the purposes of the CAP Code; the brand also needs to have some sort of control over the content.

We know that a recommendation from someone you trust will often make you more likely to make a purchase or get you to check out a particular product, service or tool. We are likely to see it every day on Facebook with their recommendations feature. There, your friends will give you a word of mouth recommendation which due to the amount of trust you will have in that individual, mean you will be likely to take up their advice.

The question here is that when a brand ambassador or influencer (you can still be an influencer as a full-time teacher) makes a statement, whether paid or not, is there an ethical issue? Should I, for example, have put a hashtag or comment on this tweet I made yesterday?

I love immersive reader in Microsoft's Learning Tools – it now works in so many applications too. Find out more here: https://t.co/cDtsJMQlUD #MicrosoftEDU #MIEExpert #edtech #elearning #edutwitter pic.twitter.com/TbqrP24Nty

— ✨ Mark Anderson ✨ (@ICTEvangelist) November 14, 2019

Now, the statement is completely true. I do love Immersive Reader. I think it opens up resources to learners that might not have otherwise been able to access them. It’s free as part of Microsoft’s offer to education. I was not paid to make that statement. It is essentially a gif of a slide I share sometimes at events. Should I have made a statement in that tweet? I don’t know the answer, but ethically, perhaps I should have.

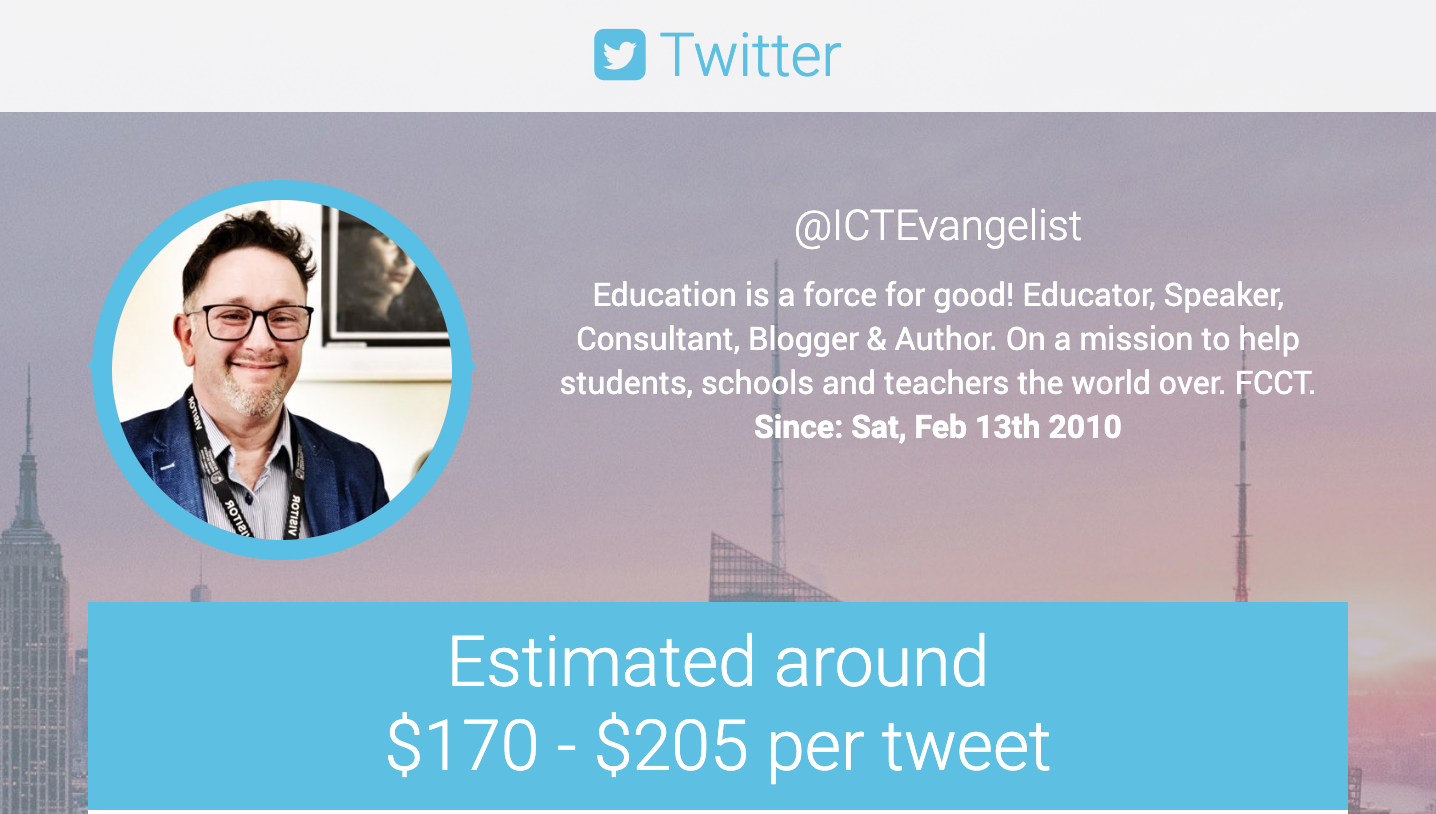

I recognise that in my position with a few followers on social media, I am an influencer. As shown by ‘webfluential’s influence estimator‘… you might like to have a look at that yourself too.

Ambassadorial marketing is an extremely cheap way for edtechs to raise the profile of their products. A recommendation or referral from people you trust either in your district or on social media can seriously help drive sales, downloads, usage, product awareness and more as outlined clearly in Singer’s article:

“The competition for these teacher evangelists has become so fierce that GoEnnounce, a one-year-old platform where students can share profiles of their accomplishments, decided to offer a financial incentive — a 15 percent cut of any school sales that resulted from referrals — to Ms. Delzer and a few other selected teachers just to try to keep up with rival companies’ perks.

So far, no teacher has asked for the payment, said Melissa Davis, GoEnnounce’s chief executive. Still, she said, teacher referrals accounted for 20 percent of GoEnnounce’s first-year sales.”

So what?

I think edtechs need to get smarter about this, sooner rather than later. It will only take a few test cases and prosecutions for it to disrupt the already muddy ethical waters in which edtechs and their ambassadorial marketing schemes lie.

So what can we do about it? Well, on the flip side, I think that closer regulation, scrutiny and guidance would be so helpful.

Given the huge value that educators bring to supporting companies with:

- how they develop their products

- how teachers can use their products

- and improve the sales of their products…

…perhaps this all could be seen as a huge opportunity for schools to recognise the role they play and seek proper remuneration for their support that is more than simply ‘swag’ of some pens or mugs?

The work (and it really is work) that educators are doing all across #edutwitter should be rewarded accordingly. The carrot from edtechs of building plans and creating opportunities for mutual growth that are shared to these ambassadors need to be transparent, above board and clearly explained – as the ASA say; legal, decent, honest and truthful.

As we all know, budgets are tighter than ever for schools so perhaps this is a way of bringing in more investment into schools to support their various activities.

I think the point I am trying to make here is that the activities aren’t necessarily wrong, particularly when looking at schools as businesses, (which they are in addition to being centres of learning) the key point is, as the ASA’s strapline suggests. Make it, “Legal, decent, honest and truthful” and I think, transparent.

If schools can get savvier to this and understand the value that they and teachers bring to raising the profile of products then, that can be a good thing. It sure is murky water though.

Further reading:

- Ambassador, You’re Really Spoiling Us [Mark Anderson ICTEvangelist, 12 September 2017]

- Silicon Valley Courts Brand-Name Teachers, Raising Ethics Issues [New York Times, 2 Sept 2017]

- Responding to Ethics Concerns About EdTech [Sean Arnold, 2 Sept 2017]

- Some Thoughts on the “Edupreuner” #EdChat [Nicholas Provenzano, 2 Sept 2017

- The Dilemma of Entrepreneurial Teachers with Brand Names [Larry Cuban, 5 Sept 2017]

- The Fault Lines Between Sharing and Shilling for an Edtech Product [EdSurge, 5 Sept 2017]

- Educators as Ed-Tech Company Brand Ambassadors Raises Ethical, Policy Questions, Report Finds [EdWeek Market Brief, 17 Jan 2017]

- Why do edtech folk react badly to scepticism? Part 1: Vested interest [David Didau, February 20th, 2016]

- The FTC’s Endorsement Guides: What People Are Asking [Federal Trade Commission, Sept 2017]