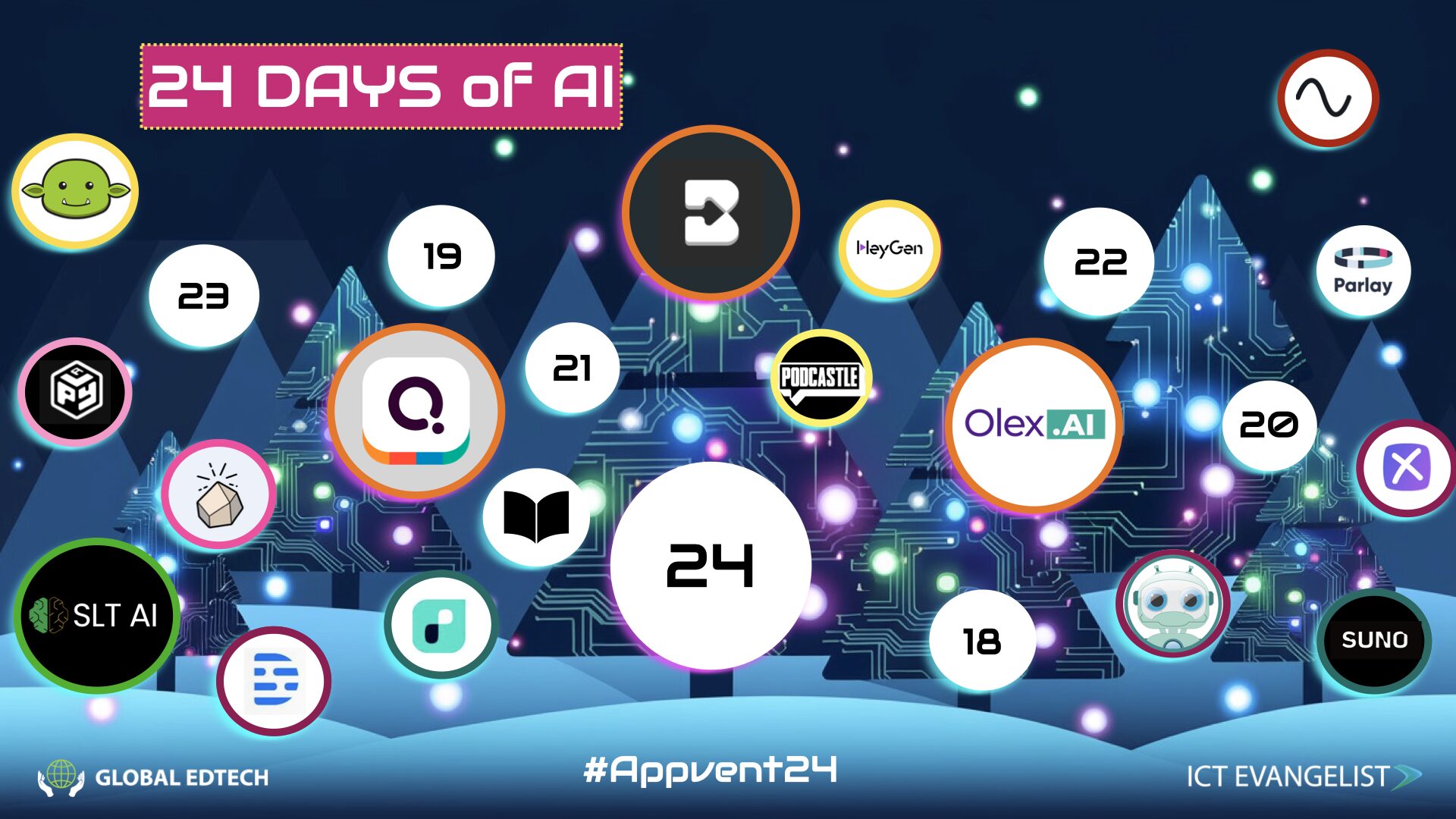

Welcome to Day 17 of this year’s #24DaysOfAI Appvent Calendar.

In a pivot to our usual posts about Ai tools and platforms, today I share a working paper that I feel should be essential reading for everyone working in education.

Why is the paper important?

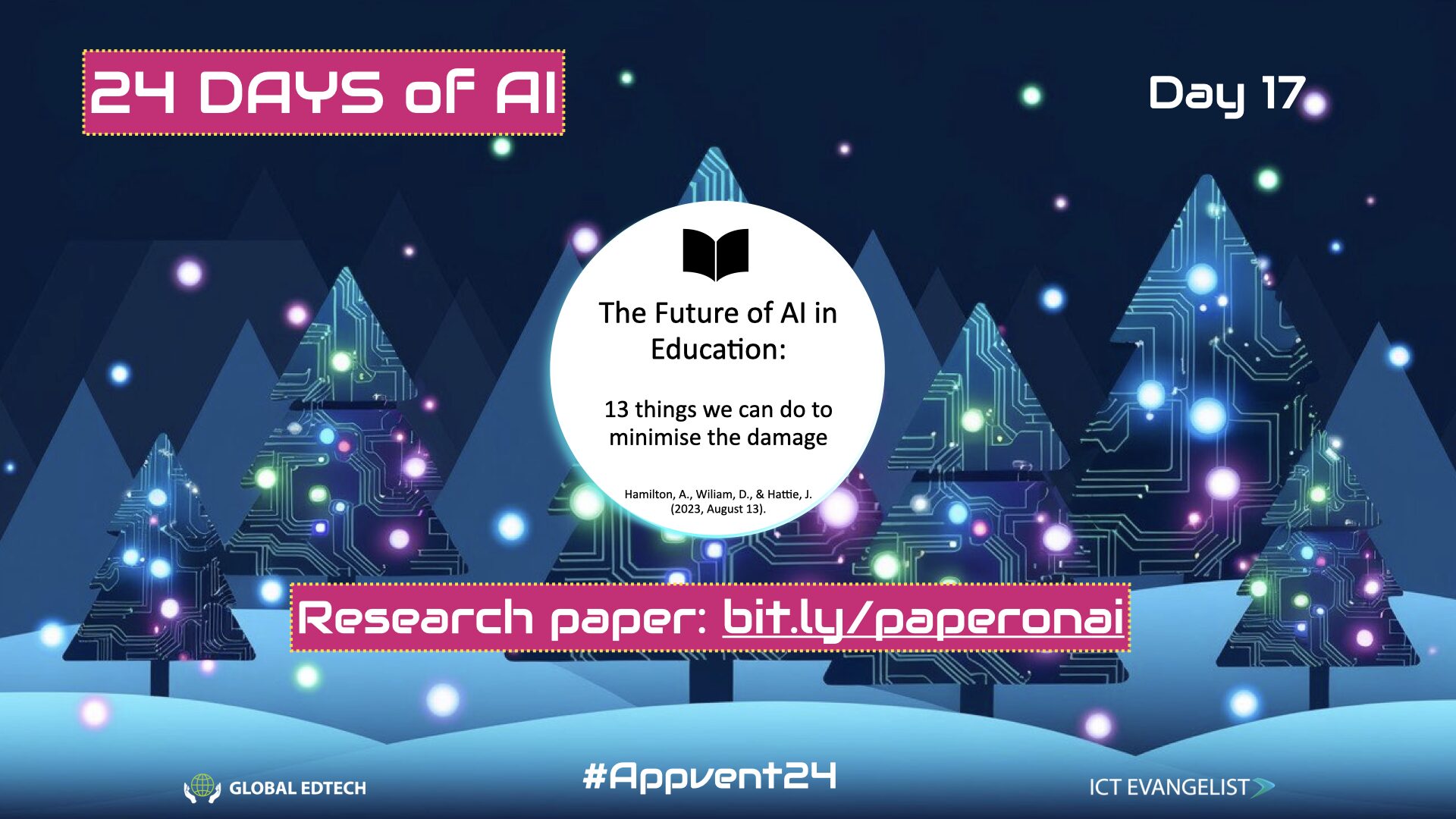

Originally shared some 16 months ago, Arran Hamilton, Dylan Wiliam and John Hattie wrote a working paper titled: “The Future of AI in Education: 13 Things We Can Do to Minimize the Damage”.

Even though it was written and shared more than a year ago, I am still surprised when I talk to people in schools the world over, that they haven’t read it. It is for this reason, that I decided to share today not an app or a tool or a platform to jump on, but something far less Ai, than Ai. A solid clarion call, written by some of the most respected people in the world of evidence in education.

Even if we take the following paragraph from the very comprehensive paper (it’s quite a long read at 39 pages, 45 if you include references) it is both my surprise at the lack of people who’ve heard of it all this time on and their final sentence that reads:

“…we need to get moving now!”

That has led to me wanting to share about it with you now as their 13 pieces of advice that they share, don’t seem to be being acted upon!

Each day on social media I see people sharing (me included) posts about the latest Ai development, and it is true, the developments are amazing. From Sora’s launch to the general public this week, to Hailuo AI last week – the pace at which technology is being developed is phenomenal. Just last week, Alphabet (that’s the company behind Google if you didn’t know) announced Willow. Have you heard about it? Willow is Alphabet inc’s new quantum chip. “What’s a quantum chip?” I hear you ask… well that’s a whole other blog post in itself, but in short, it’s a new type of computer chip that blows everything you’ve ever known about computing and processing power out of the water. In this article Google shares that:

“Willow performed a standard benchmark computation in under five minutes that would take one of today’s fastest supercomputers 10 septillion (that is, 1025) years — a number that vastly exceeds the age of the Universe.”

I had to read it twice…

“Willow performed a standard benchmark computation in under five minutes that would take one of today’s fastest supercomputers 10 septillion (that is, 1025) years — a number that vastly exceeds the age of the Universe.”

Of course, you can’t pick one of these up at PC World (yet) but this work is a significant milestone to us being in a place where this kind of computing power will exist, in our lifetimes. Science fiction has become a science fact many times in my lifetime, and it continues apace and they expect us to have this technology available in 5 years.

(Made using Microsoft Designer inspired by the quote “Science fiction has become science fact”)

So, in a world where we are looking at having access to this kind of computing, it’s fair to reflect just like Hamilton, Hattie and Wiliam do in their paper that:

“We should work on the assumption that we may be only two years away from Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) that is capable of undertaking all complex human tasks to a higher standard than us and at a fraction of the cost. Even though AGI might still take several decades, the incremental annual improvements are still likely to be both transformative and discombobulating and this requires our collective attention now.”

Why is looking back a helpful way to look forward and why is that important with this paper?

One of the most valuable things about this working paper is how Hamilton, Hattie, and Wiliam use the past to help us better understand the present and prepare for the future. When we look back at previous innovations; farming, the industrial revolution, the calculator, it’s clear that every technological leap has had profound and often unexpected consequences for society, work, and education.

Take the calculator. When it first emerged, it was seen as a threat to mathematical skills in the classroom. “Students will forget how to do maths!” people cried. Instead, calculators changed the landscape of what was possible. Teachers focused less on rote arithmetic and more on problem-solving and critical thinking. Yet, that shift didn’t happen overnight, and not everyone adapted smoothly. The lesson here? Every time a new technology disrupts the status quo, education must respond thoughtfully and deliberately to ensure it enhances, not diminishes, learning.

The same was true for farming. The agricultural revolution transformed society, freeing people from subsistence living. It created space for innovation, yet also caused significant displacement and disruption. With AI, Hamilton, Hattie, and Wiliam argue that we are standing at a similar crossroads except this time, the pace of change is faster than anything we’ve experienced before.

The paper’s power lies in this comparison to history. It reminds us that change isn’t inherently good or bad, it depends on how we respond.

If we look back, we see the cost of inaction and the importance of being proactive.

If we fail to apply the lessons of the past, we risk being caught flat-footed as AI reshapes our schools, our workforce, and our world.

Remember, Blockbuster had the chance to buy Netflix for $50M in 2000, if they could go back in time, what do you think they’d do? The lesson here for education should be clear; failing to adapt could leave us irrelevant in a rapidly changing world, much like Blockbuster.

This isn’t about resisting technology, nor is it about rushing to adopt every shiny new tool. It’s about ensuring that AI works for us, not the other way around. Hamilton, Hattie, and Wiliam invite us to act now before decisions are made for us, not by us. On this point, I often share this image in my presentations to highlight the point – recognise it?

Five Things All Educators Should Learn From This Paper and Act Upon

The working paper The Future of AI in Education: 13 Things We Can Do to Minimise the Damage offers 13 critical recommendations, but from my synthesis of the paper, here are five that I believe every educator should reflect on and act upon immediately.

For sure, there are many other things I could share and talk about such as the impact of using Ai by novice teachers vs expert teachers and much more, but you really should read the paper (bit.ly/paperonai).

The truth is, these aren’t theoretical ideas, they are actionable steps that can help you navigate the complexities of integrating Ai into education responsibly, effectively and hopefully, equitably.

1. Be Critical, Not Passive, About Ai Adoption

Too often, new technologies are adopted without enough thought about their actual impact. The paper urges educators to actively evaluate Ai tools, asking tough questions about their pedagogical value and potential unintended consequences. This is essential because not every shiny new tool will genuinely enhance learning or reduce workload.

Teachers and school leaders need to take control of the narrative around Ai, ensuring that its adoption aligns with educational goals rather than being driven by external pressures. As the authors highlight, we need to be proactive, not reactive, in determining how Ai fits into our schools.

What this means for schools: Develop a clear framework for evaluating new technologies. This could include criteria for assessing their impact on teaching and learning, as well as their alignment with the school’s broader strategic goals.

2. Prevent Ai From Exacerbating Inequalities

The digital divide is not new, but Ai risks deepening it further if we are not careful. The paper stresses the importance of ensuring equitable access to Ai tools, training, and infrastructure for all students, regardless of their socio-economic background.

This is particularly important for schools serving disadvantaged communities. Without intervention, we risk creating a two-tier system where some students benefit from cutting-edge technology while others are left behind.

What this means for schools: Conduct regular audits to identify gaps in access to technology within your school or trust. Advocate for targeted funding to address these disparities and ensure all students have the opportunity to benefit from Ai.

(Made using Dall-E 3)

3. Empower Teachers Through Professional Development

Teachers are the cornerstone of education, and their role becomes even more vital as Ai tools are introduced into classrooms. The paper emphasises that professional development should focus not just on how to use Ai tools but also on how to integrate them effectively into teaching.

This aligns perfectly with my own belief that technology should support teachers, not replace them. Teachers need the confidence to make informed decisions about Ai, understanding both its potential and its limitations.

What this means for schools: Invest in high-quality CPD (ahem!) that prioritises the pedagogical use of Ai. This should include training on evaluating Ai outputs, safeguarding, and using Ai tools to enhance specific teaching strategies.

4. Act Now to Shape Ai’s Role in Education

One of the most striking messages from the paper is its sense of urgency. The authors argue that we cannot afford to wait until Ai’s effects are fully realised. By then, it may be too late to influence how Ai is used or to mitigate its risks.

This is not about rushing into decisions but about taking deliberate, thoughtful action now. Schools and educators need to be part of the conversation about Ai, ensuring that their voices are heard in shaping its role in education.

What this means for schools: Establish Ai strategy groups that bring together teachers, leaders, and (importantly) students to explore how Ai can be used effectively and ethically. Use these groups to stay ahead of developments and influence wider conversations about Ai in education.

5. Draw Lessons From History

The paper draws parallels with past technological revolutions, from the Industrial Revolution to the advent of the calculator. Each brought significant disruptions but also opportunities for those who adapted thoughtfully. The same is true for Ai.

Looking back helps us anticipate potential challenges and opportunities. For example, when calculators were introduced, educators initially resisted them, fearing they would undermine basic maths skills. Over time, however, calculators shifted the focus from arithmetic to problem-solving. The key was thoughtful integration, a lesson that applies equally to Ai.

What this means for schools: Use historical examples in CPD sessions to help educators contextualise Ai’s potential impact. This can foster a balanced perspective, showing that while change is inevitable, it can be guided in ways that benefit students.

Final Thoughts

These five takeaways are just a small part of my learning and synthesis from the paper. Yes, the paper offers 13 detailed recommendations, each of which deserves attention. However, if there is one overarching message, it is that we must act now. Ai is not another educational trend, it is a transformative force that could either enhance or undermine our work; it all depends upon how we approach it. The authors offer actionable strategies that schools and educators can start implementing today. This paper is essential reading for anyone serious about ensuring Ai supports education, not disrupts it.

For the full list of recommendations and more details, download the paper here: bit.ly/paperonai.