Whether you like it or not data and knowing how to understand, interpret and analyse it is an important facet of the modern educator. There are lots of systems that you probably use every day that hold lots of data; you’ve probably had about 4235242 emails from them recently about GDPR too but knowing how to take that information and turn it into something usable is littered with difficulties.

- is the data being viewed valid or does it come from unreliable sources e.g. lesson observations

- can you use the software to extract the data you need

- are you comfortable using software such as Excel, Numbers or Google Sheets to a sufficient level to make IT work for you?

With my Computing teacher hat on, something I cover quite early on in the curricula is the important idea and difference between data and information. Essentially, data is information without a context. If I say the number 13 to you, you might come back and tell me something about it being unlucky, but the truth is you won’t know what I am on about until I give it context. Once it has context, it becomes information.

There are lots of different ways that once we understand this clear distinction we can use this to help us. Using technology isn’t the only way that we can use data to help inform us about our learners in the classroom. As we work with our learners, complete tests using ideas from retrieval practice, get scores from these tests, etc, it doesn’t take long for us to gather lots of data but this isn’t the whole picture and doesn’t need to use technology either (although it can help lots especially if there are sums involved!).

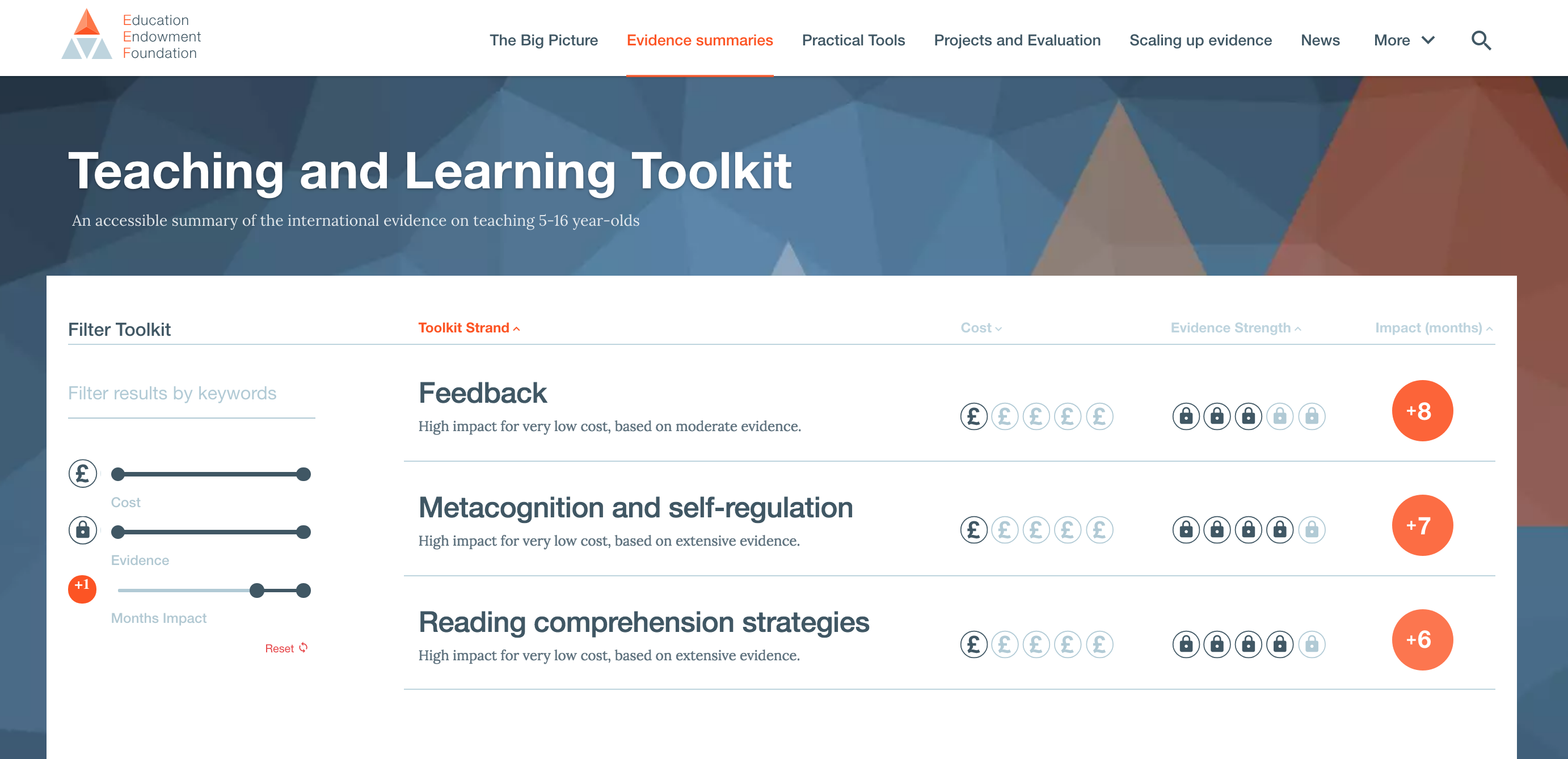

As you will know from the research of the Education Endowment Foundation, metacognition and self-regulation have a very high impact with low cost based upon extensive research. A key element to learners being able to make the most of these strategies and learning about how to learn well in your subject comes from your strong relationships with those learners. Hattie demonstrates this importance too, giving metacognition and self-regulation high scores as well as teacher credibility and teacher estimates of student ability. With this in mind, it goes to show exactly how important our contextual knowledge of our learners is. What can we do with this knowledge now that we know all of these things?

What to do?

So this is all very good but what advice can we take from it to inform how we can turn evidence into practice so it informs what we do?

- Know your learners. Forge strong relationships with them.

- Be consistent. Do what you say you’re going to do so that you engender teacher credibility.

- Make sure you have conversations with your learners about learning and their progress. Elicit information from them. If you are finding that your learners disengage with their studies once they have received a test score that is indicative of an environment where learners are not engaged in the learning process. If this is the case, then don’t tell them the score. Engage in a conversation about the test, about the answers, about the larger areas of misconception within the group. It is throug these conversations you will help provide interventions for your learners, regardless of them ever being given a test score.

- Share with your learners the best ways to learn. Teach them self-regulation strategies such as using retrieval practice to support with their revision of topics but don’t just do this as homework, do it in class first to help them gain the right habits of learning. Mirror this with other strategies so learners develop in their awareness of cognitive psychology principles (and don’t end up with cognitive overload!).

- Use your systems (with or without technology) to keep a record of where your learners are at. If you are a secondary teacher this is particularly important given the volume of learners that will pass through your classroom in any given week. Free your mind up a bit by keeping records, contextualising your students so that they aren’t just data but individuals.

How can technology help?

Well, it wouldn’t be a blog post from me without some recommendation around technology, would it? The aforementioned programs, Excel, Numbers and Google Sheets all have simple spaces where you can add data in, where it can be manipulated and where you can easily add comments and collaborate on the information too if required. Without any actual calculations included, my last team found using Google Sheets an invaluable tool for tracking the progress of our learners in our GCSE group. We were able to see how each student was performing at any given time and easily add comments to any of the data we added to the spreadsheet to help contextualise the data.

For some people reading this you might be thinking to yourself, well…. yes…. obviously…. we’ve been doing this for ages. Well if you have then great – as I always say, making an impact with technology doesn’t have to be a difficult thing, you can just use the software like a bit of paper, just that it’s a bit of paper that you don’t have to carry around with you and can be accessed from anywhere in the world so long as you have an internet connection.

If you’d like to learn more about how you can use these different tools beyond how I’m discussing them here, there are lots of training materials available via Google, Microsoft and Apple:

There are some fantastic things you can do to manipulate the data to extrapolate trends and do all sorts of whizzy things. The important thing I would suggest to you though is whilst it is important to be able to contextualise your data, make sure your learners and your relationships with them are your focus. Technology sure is whizzy but it is in knowing your learners and working with them closely on what it is to be a good learner that is important, not whether you’re able to create pivot tables and create different scenarios for your groups.

Thanks for reading my post, I hope you’ve found it useful.